The Baron: Syria's First Hotel After the War

WORDS AND PHOTOS Zila Demirjian

Every Syrian with roots in Aleppo has heard of the old hotel in the Aziziyah district. It’s one with the city the way laurel soap or pistachios are. Many know it as the place where Agatha Christie stayed while her husband completed his archeological work in the region. It is also where King Faisal declared Syria’s independence – from the balcony of room 215 to be exact. An unassuming building from the outside that easily blends into the bustle of the crowded market, one would not think of the Baron as one of the first hotels in the Middle East at first glance. But the closer you get, the finer the details.

Before the Baron Hotel, there was Ararat Hotel, the Mazloumian family's first attempt at establishing luxury accomodation in the region at the end of the nineteenth century. In 1909, Onnik and Aremenak Mazloumian expanded the business with the Baron. To understand the importance of this venture, one would only need to compare it to the largest caravanserai in Syria, Khan As'ad Basha Al-Azem, in the old city of Damascus. The traditional lodging for Europeans and travelers at the time, it was made up of small rooms fitted next to each other where one could meet their basic needs, such as food, water and fodder for animals – somewhere that is more practical than comfortable.

A Visit to Aleppo’s Baron Hotel

The first time we visited the Baron Hotel was in the Summer of 2021, which marked a year since my family moved back to Aleppo from Lebanon. The city felt foreign, as though someone had turned it inside out in the nine years we had been absent. A hundred changes that we never got to witness had buried everything familiar, and for a while, we were foreigners in our own country, searching for something that could revive an old sense of belonging. It was a tedious procedure that required a personal excavation. My sister and I resolved to spend those three months getting our hands on anything and everything that could help our cause. We spent a day roaming the Citadel of Aleppo under the scorching August sun.

We traveled more than five hours to tour the Krak des Chevalier near Tartus. We visited the souks in the heart of old Aleppo, the public gardens built during the French occupation, and every local art exhibition we heard about. It was not until we stumbled upon the Baron Hotel that the pieces clicked.

The hotel was suspended in a pocket of time, in the interval between what many people consider the golden age of Aleppo and its rapid decline. You would not think the establishment had been the target of repeated shellings if not for the physical evidence. Instead, it felt as though, due to a cosmic fluke, all the customers had vanished and everything was left untouched for their return.

The reception area was still stocked with postcards and maps of Aleppo. The shelves of the bar were brimming with bottles and memorabilia. There were chairs for every table in the breakfast room, and there – blocking the entrance to the restaurant – was a big wine barrel with a laminated sign celebrating the hotel’s one-hundredth anniversary the same year that the war broke out.

A man who we later found out was the resident guard opened the door and let us inside, but we only made it as far as the lobby, where we waited while he went further in to inform someone of our arrival. The woman who emerged from one of the side rooms must have been in her sixties.

When we expressed our interest in looking around the hotel, she asked if we were photographers or reporters. Roubina Tashjian-Mazloumian was the late owner's wife who had taken up residence in the hotel.

“I don't invite just anyone inside, but I guess I'll make an exception today,” was her introductory line that morning and on the two other occasions we met. Though the words might not seem welcoming, an ibrik of coffee was always ready on the stove, and a patched-up chair in the most scenic part of the room awaited a visitor.

The first time we went to the Baron Hotel, we were accompanied by a law student who had come from Damascus to take her final exams. She was staying nearby and visited the hotel every morning. She knew it inside out, as though she were the manager herself. She told us about Damascus: the easiest way to get there and must-see sites if we were to make the trip there.

As for Mrs Mazloumian, we discovered that she had gone to university in Lebanon during the civil war. Hamra was one of her favorite neighborhoods, and it seemed as though the war never managed to erase the beauty of Lebanon from her memory.

It all felt very natural. The core of the hotel is not just its eventful past, but the people who fill it.

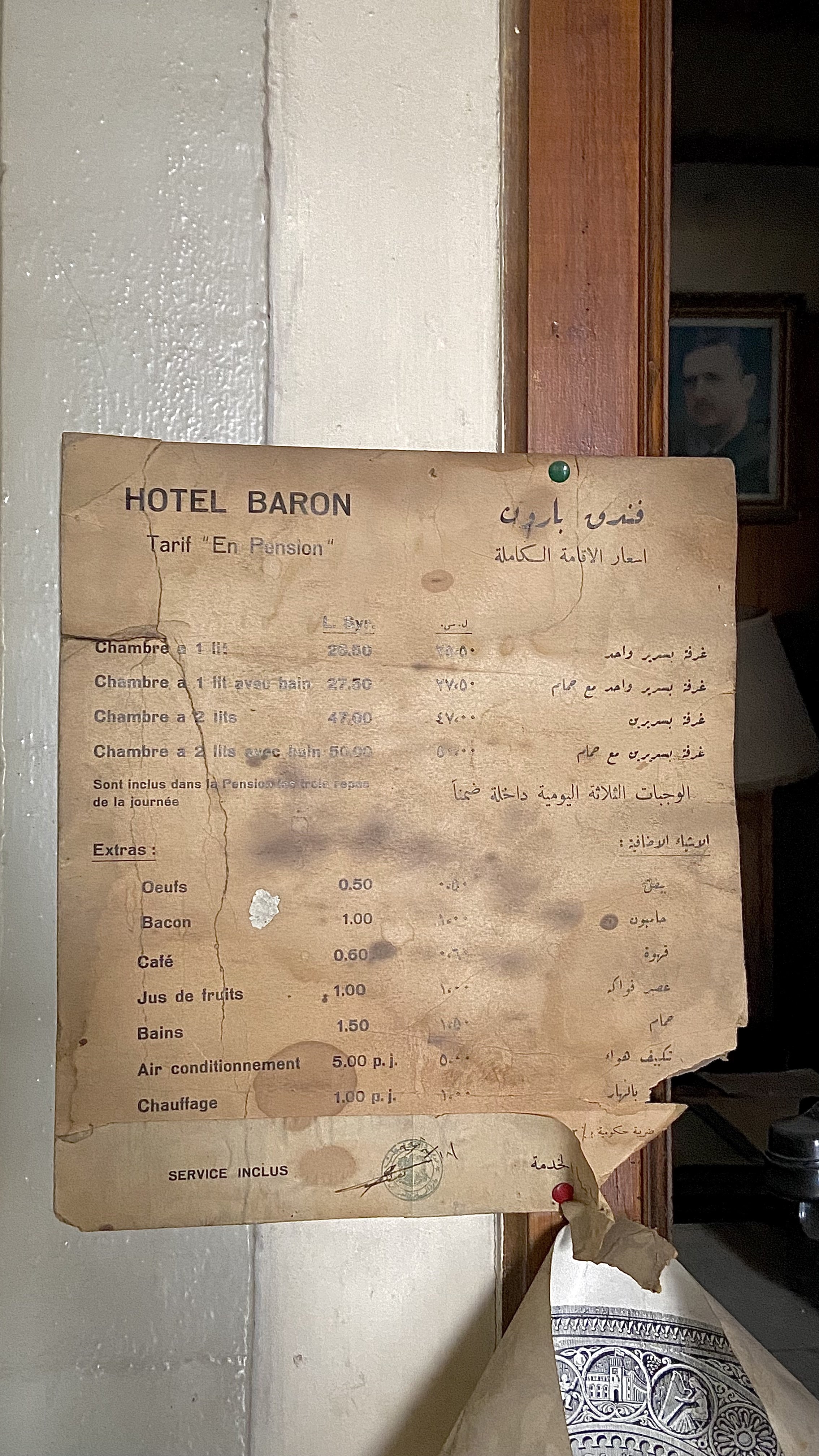

Though The Baron Hotel is not particularly large – it comprises seventeen rooms – its rich history expands and contorts the space. After we drank our coffee, Mrs Mazloumian offered us a tour, which was more than we could have ever expected. She encouraged me to take pictures and took us through the reception area. On the wall was a guide for tourists and a menu that must have been several decades old on which all the prices were listed. A single room cost 40 Liras, breakfast included.

When it started operating, the Baron was one of its kind. A large framed picture in the lobby depicted the hotel as the gateway to the east, with its arched entrance posed between the Citadel of Aleppo and two men garbed in traditional attire, accompanied by a camel. Below, the Baron Hotel was advertised as a “first-class establishment that boasted a central heating system”. Not only was it the first to have warm bath water, but the Baron was considered one of its kind because it had introduced a new level of comfort which was nonexistent in the caravanserais.

During the war, the hotel opened its doors to refugees despite receiving five mortars that brought the plaster off the walls.

“The bombing was so close that it would shake the entire building,” Mrs Mazloumian said while she was showing us the bar. “This room used to be beautiful. Look at the floor. You don’t see people using colorful tiles like this anymore.”

The hotel received its last customer in 2019. A French group insisted on staying despite being informed there would be no warm bath water or electricity. According to Mrs Mazloumian, they had breakfast together on the patio overlooking the street every morning, free of charge.

She showed us her late husband’s photography – black and white pictures of citadels and historic ruins. “I love photography too, but not as much as he did. His father was a photographer as well.” She showed us old pictures of bartenders and customers and knick-knacks collected over time, such as an illustrated map of Syria where the columns of Palmyra looked like its center of gravity.

Upstairs, we checked the bedrooms one by one, our guide pointing them out not by number but by the names of the important personalities that had stayed there. Agatha Christie, Lawrence of Arabia, Charles De Gaulle, Gamal Abdel Naser, David Rockefeller, and many more.

All the beds were neatly made, and every room included a telephone that came with a note: lift telephone and listen. As though a concierge was waiting on the other end.

During the war, when the hotel had been closed to customers, it received a visitor: a young man who had sat in the breakfast room until Mrs Mazloumian was able to join him. His father had been the ambassador of a European country to Syria, and he had spoken so fondly of the hotel that his son had made it a point to visit at his earliest convenience – a testament to the hotel's place in history and in people's memory.

War has brought the plasters off the walls. It has made the third floor of the building uninhabitable. It has almost erased a cultural asset that had witnessed the Ottoman rule, the French occupation, and a series of volatile regimes. And yet, The Baron Hotel has left its mark on Aleppo and the region by acting as a gateway to this rich part of the world.